It has long been my belief that pulp fiction not discovered by age thirteen was beyond my ability to appreciate later. A certain amount of nostalgia seemed essential to enjoying the material once age and responsibility have got the better of you in life. There are, of course, exceptions to this rule in the rare instances where genuine literary talent was on evidence as is the case with the Holy Trinity of Hardboiled Detective Fiction: Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and Ross Macdonald. Given that my first two Seti Says posts concerned Bram Stoker's Dracula, I decided to revisit Peter Tremayne's three Dracula novels and one short story that I enjoyed so much as a teenager to see how they held up three decades on.

Peter Tremayne is best known today for his long-running Sister Fidelma mysteries. His medieval detective series is sort of a lightweight version of an Umberto Eco doorstop. Although Tremayne's real world credentials are quite impressive as both an academic and scholar, his fiction is strictly populist in its appeal. Turn back the clock 35 years and one would find Peter Tremayne as a dedicated pulp pastiche writer trying his hand at extending the lifespan of H. Rider Haggard's She Who Must Be Obeyed, deliriously combining Shelley's Frankenstein with Conan Doyle's Hound of the Baskervilles, and delving deep into Stoker's Dracula for a trilogy of loosely connected books published by Bailey Brothers in the UK.

The first of the trilogy, DRACULA UNBORN (US title: BLOODRIGHT) was written in 1974 and first published in 1977. Tremayne starts the story off with the author himself discovering a manuscript belonging to Stoker's fictional Dr. Seward at a swap meet in Islington. The manuscript is a translation by Professor Abraham Van Helsing of a late 15th Century memoir of Mircea Dracula, the youngest son of the historical Vlad Tepes. From there the story moves rapidly from the modern world referencing Stoker and actual Romanian history to Mircea's autobiography which reads, in the first few chapters, like a pastiche of a classic swashbuckler. Mircea is living a nobleman's life in Rome as Michelino. He has been raised in Italy after his mother fled Wallachia when he was a small child. Michelino is just the sort of rogue favored by Dumas or Sabatini in the fiction of the past two centuries. He is an excellent swordsman lacking in all scruples who thinks nothing of seducing a married woman as a means of settling a score with her husband. Fleeing an assassin set on his tail by the cuckolded husband (it's an unwritten rule that such characters never consider consequences of their actions), Michelino reverts to his true identity as Mircea Dracula and returns to the family home in Wallachia and Tremayne is ready to switch genres on the reader yet again.

Moving from the splendour of Roman villas to hoary old Transylvania with it's superstitious villagers and cobwebbed castles, Tremayne fails to evoke the effectiveness Stoker demonstrated in contrasting the New World with the Old. Instead the reader is given the awkward feeling of channel surfing between old movies. Part of the problem is the overall familiarity with the material. Tremayne recycles incidents and dialogue from Stoker's book and evokes scenes from Universal Horrors of the thirties and forties and from Hammer Horrors of the fifties and sixties. It must be said, to his credit, that upon publication DRACULA UNBORN was virtually unique. It may very well have been the first novel to fully integrate Stoker's vampire with the historical despot known as The Impaler. Today, the well-read Dracula aficionado will recognize Radu Florescu and Raymond McNally's research on Vlad Tepes is regurgitated nearly word for word in the pages of Tremayne's book. Its greatest interest lies in spotting the similarities (likely coincidental) between it and Jeanne Kalogridis' DIARIES OF THE FAMILY DRACUL trilogy from the nineties (books that are far too derivative of Anne Rice's LESTAT series for my taste despite Kalogridis' talent as a writer).

Tremayne improved the second time out with THE REVENGE OF DRACULA. Despite the rather silly title and even more raiding of lines and incidents from Stoker and monster movies of decades past, this is a great pulp novel. I would go so far as to say that I was sorry Tremayne tied Dracula into the proceedings at all as it would have stood alone easily as a thrilling weird mystery with no need for the vampire count to make an appearance. Once again, Tremayne starts the story with the author himself receiving the manuscript. This time, the story originates with a psychiatrist who takes the author to task for writing horror fiction by demonstrating the negative impact such work can have on impressionable minds in the form of a 19th Century memoir by one Upton Wellsford, a Vicar's son who toils in a lowly clerical position in the Foreign Office.

Upton has little use for God or country and consequently, is destined to pay the price for his arrogance. Of course, before the natural order is restored we get plenty of fun along the way. Upton buys an antique at a curio shop. A carved dragon that he suspects is Chinese in origin and, more importantly, pure jade despite the shopkeeper's ignorance. Gloating upon his valuable find, Upton is troubled by insomnia and strange dreams from this point forward in the narrative. Upton's recurring dream is that he is a Pagan priest set for sacrifice by a beautiful Pagan priestess. Of course, Upton is the reincarnation of an honorable Egyptian priest, Ki who was sacrificed to the demon, Draco by his lover, Queen Sebek-nefer-Ra centuries before. In due course, Upton meets his dream girl, Clara Clarke and falls in love. She is the reincarnation of Sebek-nefer-Ra and has been sharing the same recurring dream as Upton. Along the way we meet Upton's best friend, an amateur occultist who foolishly thinks he can contain the power held in the jade dragon and the Foreign Office sends Upton packing to Romania to attend a Coronation. By the time, Dracula turns up you're actually resentful. Tremayne does such a great job evoking the weird fiction prevalent in the first half of the last century that the vampire Count isn't needed. Tremayne takes the reader along on an emotional roller coaster as Upton and Clara barely escape Dracula with their lives only to suffer hardship in later years before coming to a tragic end. It's a bit of a downer, but a nice sting at the end with the psychiatrist's letter to Tremayne deriding horror fiction as utter nonsense worthy of scant attention.

A peculiar postscript of sorts exists with Tremayne's short story, "Dracula's Chair." He definitely suffered for poor titles early in his career. This short piece is largely unintelligible to the reader who hasn't read THE REVENGE OF DRACULA, but it would have been one wrinkle too many had it been included as a further epilogue as Tremayne originally intended. Once again, Tremayne places himself in the story as his wife picks up a Victorian chair for him at an antique shop. Once seated in the chair (which belonged to Upton Wellsford, ironically), Tremayne and Wellsford mystically switch souls with Tremayne fated to die at Dracula's hand in Wellsford's body at the horrific conclusion of THE REVENGE OF DRACULA with the knowledge that Wellsford has escaped death to live his life as Peter Tremayne, bestselling author in the 20th Century.

Tremayne's final visit to the character was with DRACULA, MY LOVE. Once again, his predilection for dreadful titles hampers him. The cover art and jacket blurb for the UK edition promise a Victorian version of TWILIGHT with Dracula falling in love with a proto-feminist. Happily, the book isn't quite that bad. This is really a novella rather than a full-length novel. Tremayne is back to introduce the novel as he is visited by Serban Mitikelu, a Romanian monk who shares with him the memoir of Morag MacLeod, a Victorian Scotswoman. The monk is killed by a vampire after leaving Tremayne's apartment. This is revealed at the end of his introduction instead of saving it for a suitably creepy ending.

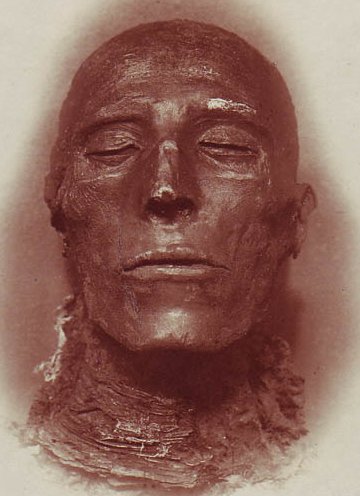

Morag's life reads like a bowlderized version of Victorian pornography as she suffers rape and maltreatment at the hand of one cruel lord and squire after another. Happily, these details are not explicit, but are still unpleasant enough to make the reader feel queasy that it is being used as entertainment. Of course, if there's one thing Tremayne can be counted on for it is giving his libertine characters a proper Victorian comeuppance and Morag is no exception. When she falls in love, you can bet she will become pregnant, the father will die before they can wed, and his family will disown her as the harlot who seduced their son. Inevitably, Morag finds her way to Transylvania and Castle Dracula. The third time round, Tremayne's take on Stoker's household is so familiar that the over-familiarity kills it. There is a romance between the two, but it is not as much Barbara Cartland as the jacket blurb scares the reader into expecting. What really kills the book is Tremayne's insistence on shoehorning the historical Countess Elisabeth Bathory with Abraham Van Helsing into the proceedings. I know he's trying to set up Stoker's book (Kalogridis took much the same tact with her trilogy), the trouble is (as with Kalogridis) they make too much of Dracula's family and homelife. The sheer number of characters and knowing their muddled history (Dracula is actually Egyptian, not Transylvanian) makes you wish he had decided to use all original characters because in the end, Tremayne's take is his own and bears little resemblance to Stoker outside of what he chooses to steal. I happily choose pulp fiction over literature any day, but much as it pains me to say, Tom Wolfe was right, sometimes you can't go home again. Despite a near perfect pulp novel in the second book, Tremayne's trilogy (and one odd story) are not worthy of Dracula's noble title. I'll give his efforts two out of a possible five Mummies.

The remainder in

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment