Showing posts with label thriller. Show all posts

Showing posts with label thriller. Show all posts

Friday, December 5, 2014

Blogging Sax Rohmer…In the Beginning, Part Five

“The Secret of Holm Peel” was first published in Cassell’s in December 1912 and was the last story Arthur Henry Ward published under the byline of Sarsfield Ward [having dropped the first initial A.]. Rohmer scholar Robert E. Briney rescued it from obscurity for the 1970 Ace paperback Rohmer collection of the same name. Gene Christie later selected the story for inclusion in the first volume of Black Dog Books’ Sax Rohmer Library, The Green Spider and Other Forgotten Tales of Mystery and Suspense in 2011.

The story’s inspiration can be found in Rohmer’s article, “The Phantom Hound of Holm Peel” which was first published in Empire News in February 1938 and was later collected by Rohmer scholars Dr. Lawrence Knapp and John Robert Colombo in the 2012 Battered Silicon Dispatch Box collection of Rohmer’s articles, Pipe Dreams: Occasional Writings of Sax Rohmer. The article was later recounted by Rohmer’s widow, Elizabeth Sax Rohmer and his former assistant, Cay Van Ash in their 1972 biography of the author, Master of Villainy as well as by the aforementioned John Robert Colombo in his 2014 collection, A Rohmer Miscellany.

The story itself is a well-written Gothic romance set on the Isle of Man at the estate of Holm Peel. Rohmer brews a delightful concoction of past life obsession, a ghostly hound, the curse of a suicide, family drama, and a daring jewel heist. The trouble is the jarring changes in narrative voice give the story an awkward, at times amateurish feel that undermines the strength of the otherwise polished narrative.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE.

Labels:

pulp fiction,

Sax Rohmer,

thriller,

Weird Menace

Saturday, November 15, 2014

Blogging Sapper’s Bulldog Drummond, Part Seven – Temple Tower

Temple Tower (1929) was the sixth Bulldog Drummond novel and marked a departure from the series formula. Having killed Carl Peterson off at the conclusion of the fourth book and dealt with his embittered mistress Irma’s revenge scheme as the plot of the fifth book, Sapper took the series in an unexpected direction by turning to French pulp fiction for inspiration.

Sapper also placed Hugh Drummond in a supporting role and elevated his loyal friend Peter Darrell to the role of narrator. The subsequent success of the venerable movie series and the future controversies generated by Sapper’s reactionary politics and bigotry obscured the versatility of his narratives and led to his being under-appreciated when considered with his peers.

French pulp literature from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century was particularly rich. While Jules Verne and Alexandre Dumas remain the best known French pulp authors of the era, Paul Feval’s highly influential swashbuckler, Le Bossu [“The Hunchback’] (1857) and his expansive criminal mastermind saga, Les Habits Noirs [“The Black Coats”] (1844 -1875) did much to set the stage for Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain’s long-running absurdist thriller series, Fantomas (1911 – 1963) as well as Arthur Bernede’s seminal masked avenger Judex (1916 – 1919). Pioneering French filmmaker, Louis Feuillade adapted both Fantomas and Judex to the silent screen as well as creating his own epic Apaches crime serial, Les Vampires (1915 - 1916).

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE.

Labels:

adventure,

Bulldog Drummond,

detective,

French pulp,

mystery,

pulp fiction,

Sapper,

swashbuckler,

thriller

Saturday, September 20, 2014

Blogging Sapper’s Bulldog Drummond, Part Six – The Female of the Species

Sapper’s The Female of the Species (1928) is quite likely the best book in the long-running Bulldog Drummond thriller series. It’s one failing comes late in the narrative and spoils it as assuredly as Mickey Rooney’s bucktoothed yellow-face performance as Mr. Yunioshi sours Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) for modern audiences. As a devoted fan of both Blake Edwards and Sapper, I do my best to make exceptions for their failings, particularly when they were acceptable in the times they lived in.

In the case of the former, the suggestion of pornographic photos in Truman Capote’s novella could never have been transferred to the screen with an Asian actor in the role of Audrey Hepburn’s frustrated landlord. Edwards soft-pedaled the material and defused a scene that never would have slipped by the Production Code if handled dramatically by offering Mickey Rooney in a broad caricature of an Asian. It was a star cameo in a comic stereotype still common in television sitcoms of the 1960s and Jerry Lewis films. Audiences at the time laughed at the fact that it was Mickey Rooney making a fool of himself and nothing more. Today, the classic status of the film makes the sequence stick out as an unfortunate example of racial insensitivity in a fashion that does not taint comedies of the same era which are now considered a time capsule example of what passed for juvenile humor at the time.

So we come to The Female of the Species where Sapper’s engrossing thriller falls apart at the climax for modern readers by the repeated belittling of Pedro, an African henchman as a “nigger.” Worst of all, Sapper attempts black-face humor and notes the disguised Drummond doesn’t smell like a “nigger.” This isn’t a colonial jungle tale where the word was often employed without contempt; this is a Roaring Twenties thriller where it is used as a contemptuous slur.

While allegations of Sapper’s racism are often exaggerated by modern commentators, when he does pile it on he stands out among his contemporaries as genuinely intolerant of everyone and everything not British. Never is this more true than in this book where the sheer repetition of the slur from multiple protagonists who hold the man in contempt for the color of his skin alone leads one to feel repulsed.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE,PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE.

Labels:

Bulldog Drummond,

detective,

pulp fiction,

Sapper,

thriller

Sunday, September 7, 2014

Blogging Sax Rohmer…In the Beginning, Part Four

We already noted in our last installment that Arthur Henry Ward had adopted the pseudonym of Sax Rohmer for his relatively successful career as a music hall songwriter and comedy sketch writer. He would later claim that he worked as a newspaper reporter during these years, but that his articles were published anonymously. Allegedly he covered waterfront crime in Limehouse, but he also claimed to have successfully managed interviews with heads of state. There is little doubt the man was a great raconteur, but none of the anonymously published articles and interviews Rohmer credits himself with writing have ever been located by researchers. It is highly questionable whether he ever actually worked as a journalist or at least to the extent he claimed. What is factual is that he did begin having works published anonymously.

As a young man, he ran with a crowd of self-styled bohemians who occupied a clubhouse on Oakmead Road in London. Each member of the gang was known by rather fanciful nicknames with Rohmer being known as Digger. Their activities ran from simply hanging around the clubhouse to picking up girls and attempting various get-rich-quick schemes to avoid making an honest living. Some of their schemes were of questionable legality.

Around this time, Rohmer decided he would fictionalize their exploits. It is believed he authored seven stories about the Oakmead Road Gang. Five manuscripts were known to have survived their author’s death: “Narky,” “Rupert,” “Digger’s Aunt,” “The Pot Hunters,” and “The Treasure Chest.” All seven stories were submitted for anonymous publication to Yes and No. It appears only the first of the group of stories ever saw print. The surviving four manuscripts passed upon the death of Rohmer’s widow to Cay Van Ash. When Van Ash died in Paris twenty years ago, Rohmer's unpublished manuscripts were being held by a friend in Tokyo (where Van Ash lived for many years while teaching at Waseda University). When the friend had his visa rescinded on short notice in 2000, he was forced to leave Rohmer's manuscripts behind where they were junked by a Japanese family who thought the storage boxes contained worthless garbage.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE ON FRIDAY.

Labels:

crime,

occult,

pulp fiction,

Sax Rohmer,

thriller

Thursday, September 4, 2014

Blogging Sax Rohmer…In the Beginning, Part Three

“The M’Villin” was first published in Pearson’s Magazine in December 1906. Rohmer was still writing under the slightly modified version of his real name, A. Sarsfield Ward. The story represented a quantum leap forward in the quality of Rohmer’s fiction and shows the influence of Alexandre Dumas’ swashbucklers. Dumas remained a surprising influence on the author who still turned out the odd swashbuckler as late as the 1950s. It should also be noted that the character of Lola Dumas in President Fu Manchu (1936) is said to be a descendant of the famous author while The Crime Magnet stories Rohmer penned in the 1930s and 1940s feature Major de Treville, a character whose surname suggests he is a descendant of the commander of the Musketeers from Dumas’ D’artagnan Romances.

Colonel Fergus M’Villin may be oddly named, but he makes for a fascinating character. An expert swordsman and fencing master, he is also a bit of a cad. The story of how he comes to avenge the honor of the man he previously slew in an earlier duel maintains the breezy good humor and spirit of adventure that colors The Three Musketeers in its earlier chapters. Rohmer thought well enough of the character to have penned a sequel, “The Ebony Casket,” but it was never published. The manuscript survived up until the year 2000 when it was junked in Tokyo by a family who did not imagine its worth to collectors.

Rohmer remained proud of the story and included it in his 1932 collection of short fiction, Tales of East and West. He slightly altered the spelling of the character’s name and story’s title to “The McVillin.” It only appears in the rare UK edition published by Cassell and not the US edition or its reprint by Bookfinger. The story was not reprinted until Gene Christie collected it for the first volume of Black Dog Books’ Sax Rohmer Library, The Green Spider and Other Forgotten Tales of Mystery and Suspense in 2011.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE.

Labels:

detective,

pulp fiction,

Sax Rohmer,

swashbuckler,

thriller

Friday, August 29, 2014

Blogging Sax Rohmer’s The Shadow of Fu Manchu, Part Two

The Shadow of Fu Manchu was serialized in Collier’s from May 8 to June 12, 1948. Hardcover editions followed later that year from Doubleday in the U.S. and Herbert Jenkins in the U.K. Sax Rohmer’s eleventh Fu Manchu thriller gets underway with Sir Denis Nayland Smith in New York on special assignment with the FBI. He is partnered with FBI Agent Raymond Harkness to investigate why agents from various nations are converging on Manhattan. Sir Denis suspects the object of international attention is the special project being handled by The Huston Research Laboratory under the supervision of Dr. Morris Craig. However, Smith initially chooses to keep the FBI in the dark on this matter until he is certain.

The Si-Fan has succeeded in closing in on The Huston Research Laboratory by drawing a net around the parent corporation Huston Electric’s director, millionaire Michael Frobisher and his wife, Stella. The Frobisher marriage is not a happy one. Michael lives in fear that his flirtatious wife is unfaithful to him and Stella is likewise tormented by a series of neuroses. The family physician, Dr. Pardoe recommends an eminent European psychiatrist and Nazi concentration camp survivor, Professor Hoffmeyer to treat Stella Frobisher. Both Mr. and Mrs. Frobisher are concerned that Asians have been spying on them, going so far as to break into their home and infiltrate their country club. As their marriage is not a healthy one, neither husband nor wife confide in the other, but rather let their paranoia grow until their nerves have frayed. What neither suspects is that Carl Hoffmeyer is really Dr. Fu Manchu in disguise.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE.

Labels:

Cold War,

espionage,

Fu Manchu,

pulp fiction,

Sax Rohmer,

Shadow of Fu Manchu,

spy,

thriller

Saturday, August 23, 2014

Blogging Sax Rohmer’s The Shadow of Fu Manchu, Part One

The Shadow of Fu Manchu was serialized in Collier’s from May 8 to June 12, 1948. Hardcover editions followed later that year from Doubleday in the U.S. and Herbert Jenkins in the U.K. The book was Sax Rohmer’s eleventh Fu Manchu thriller and was also the last of the perennial series to make the bestseller lists.

The story had its origins in a stage play Rohmer had developed for several years that failed to get off the ground. It became instead the first new Fu Manchu novel in seven years, during which time the property had begun to fade from the public eye. It had been eight years since the character last appeared on the big screen and since the radio series had reached its conclusion. Detective Comics had long since finished reprinting the newspaper strip as a back-up feature for Batman. As far as the public was concerned Fu Manchu was a part of the past that seemed far removed from a world transformed by the Second World War.

The initial three novels in the series were written before and during the First World War, but were set in a pre-war Britain where the paranoid delusions of the Yellow Peril personified offered a much needed dose of escapism from the realities of war in Europe. The Yellow Peril itself was a stereotype based on a turn-of-the-century conflict that became an early example of the “foreign-other” bogeymen who would increasingly feed the fears of the West in this new century.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE,PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE.

Labels:

Cold War,

espionage,

Fu Manchu,

pulp fiction,

Sax Rohmer,

Shadow of Fu Manchu,

spy,

thriller,

Yellow Peril

Tuesday, August 12, 2014

The Long-Awaited Return of Bulldog Drummond

Even more than the sinister Dr. Fu Manchu, Bulldog Drummond has become more and more obscure with each passing decade. The original ten novels and five short stories penned by H. C. McNeile (better known by his pen name, Sapper) were bestsellers in the 1920s and 1930s and were an obvious and admitted influence upon the creation of James Bond. Gerard Fairlie turned Sapper’s final story outline into a bestselling novel in 1938 and went on to pen six more original novels featuring the character through 1954.

While the Fairlie titles sold well enough in the UK, the American market for the character had begun to dry up with the proliferation of hardboiled detective fiction. By the time, Fairlie decided to throw in the towel, the long-running movie series and radio series had also reached the finish line. Apart from an unsuccessful television pilot, the character remained dormant for a decade until he was updated as one of many 007 imitations who swung through a pair of campy spy movies during the Swinging Sixties. Henry Reymond adapted both screenplays for a pair of paperback originals, but these efforts barely registered outside the UK.

Fifteen years later, Jack Smithers brought Drummond out of retirement (literally) to join up with several of his clubland contemporaries in Combined Forces (1983). Smithers’ tribute was a sincere effort that found a very limited market to appreciate its cult celebration of the heroes of several generations past. Finally thirty years later, Drummond is back in the first of three new period-piece thrillers from the unlikely pen of fantasy writer Stephen Deas. In a uniquely twenty-first century wrinkle, the three new thrillers are being published exclusively as e-books by Piqwiq.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS REVIEW,PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE ON FRIDAY.

Labels:

adventure,

Bulldog Drummond,

detective,

Piqwiq,

pulp fiction,

Sapper,

Stephen Deas,

thriller

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

Blogging Sapper’s Bulldog Drummond, Part Five – “The Final Count”

Sapper’s The Final Count (1926) saw the Bulldog Drummond formula being shaken and stirred yet again. The first four books in the series are the most popular because they chronicle Drummond’s ongoing battle with criminal mastermind Carl Peterson. The interesting factor is how different the four books are from one another. Sapper seemed determined to cast aside the idea of the series following a template and the result kept the series fresh as well as atypical.

The most striking feature this time is the decision to opt for a first person narrator in the form of John Stockton, the newest member of Drummond’s gang. While Drummond’s wife, Phyllis played a crucial role in the first book, she barely registers in the first three sequels. One would have expected Sapper to have continued the damsel in distress formula with Phyllis in peril, but he really only exploits this angle in the second book in the series, The Black Gang (1922).

The Black Gang reappear here, if only briefly, and are quickly dispatched by the more competent and deadly threat they face. This befits the more serious tone of this book which has very few humorous passages. The reason for the somber tone is the focus is on a scientific discovery of devastating consequence that threatens to either revolutionize war or end its threat forever. Robin Gaunt is the tragic genius whose invention of a deadly poison that could wipe out a city the size of London by being released into the air proved eerily prescient.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE ON FRIDAY.

Labels:

Bulldog Drummond,

detective,

pulp fiction,

Sapper,

thriller

Wednesday, July 16, 2014

Blogging Sax Rohmer…In the Beginning, Part Two

“The Green Spider” marked Sax Rohmer’s third foray into short fiction. Still writing under the pen name of A. Sarsfield Ward, the story first appeared in the October 1904 issue of Pearson’s Magazine. It was not reprinted until 65 years later in Issue #3 of The Rohmer Review in 1969. Subsequently, a corrupted version with an altered ending courtesy of the editor appeared in the May 1973 issue of Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine. The restored text was included in the 1979 anthology, Science Fiction Rivals of H. G. Wells. More recently the story has appeared in the 1992 anthology, Victorian Tales of Mystery and Detection, the September 2005 issue of Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, and as the title story in the first volume of Black Dog Books’ Sax Rohmer Library, The Green Spider and Other Forgotten Tales of Mystery and Suspense (2011).

The story itself shares in common with Rohmer’s first effort, “The Mysterious Mummy” the presentation of a seemingly supernatural mystery that has a rational explanation. In the nine months that elapsed between the publication of “The Leopard Couch” and “The Green Spider,” Rohmer honed his writing skills and became a more devoted student of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and deductive reasoning. “The Green Spider” concerns the disappearance of the celebrated Professor Brayme-Skepley on the eve of an important scientific presentation. It appears to onlookers and Scotland Yard that the Professor has been murdered by a giant green spider that apparently made off with his corpse. The unraveling of the mystery reveals the green spider is no more authentic a threat than the phantom hound of the Baskervilles. While a minor effort, the story retains its charm more than a century on and shows that the mysterious A. Sarsfield Ward was steadily improving as an author.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE ON FRIDAY.

Labels:

detective,

mystery,

pulp fiction,

Sax Rohmer,

thriller

Thursday, July 10, 2014

Blogging Sapper’s Bulldog Drummond, Part Four – “The Third Round”

Sapper’s The Third Round (1926) marked a return to the more humorous tone of the first book in the series. Not only the humor, but the premise of that initial book is invoked with the decision to again build the plot around a spunky female whose doddering old father has fallen prey to heinous villains. All trace of The Black Gang and its doom-laden paranoia over England likewise falling prey to a communist revolution has been removed. In its place we have Hugh Drummond once again eager to escape the boredom of everyday life and engaging in comical banter with friends and foes alike.

The starting point for the adventure this time is the impending nuptials of Algy Longworth, Hugh’s old friend who has finally been reduced to the silly ass familiar from the stage play and film adaptations. The catalyst for Algy’s descent into idiocy is his having fallen head over heels in love to the extent that he now horrifies his friends by reciting poetry. So serious is his obsession with the girl of his dreams that he has become a literal walking disaster shunned by all who know him.

Algy’s future father-in-law, Professor Goodman has realized an alchemist’s dream of manufacturing diamonds at almost no cost. His intent to take this amazing discovery public brings him to the attention of the diamond syndicate who promptly hire Carl Peterson to remove this living, breathing threat to their livelihood. The novel opens with the syndicate’s interview with Peterson just as the first book opened with Peterson bringing together the international team to financiers to bankroll his scheme to destroy the British economy. Once again, Sapper deliberately echoes the introduction of Dr. Nikola in the first of Guy Boothby’s series in his treatment of the introductory meeting of the chief villain. Sapper’s decision to bring Peterson up from the background to a point of focus as the central threat for the first time is its greatest strength for his narrative finally has a focal point equal to Drummond’s often overpowering personality.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE TOMORROW.

Labels:

adventure,

Bulldog Drummond,

pulp fiction,

Sapper,

thriller

Wednesday, July 2, 2014

Blogging Sax Rohmer…in the Beginning, Part One

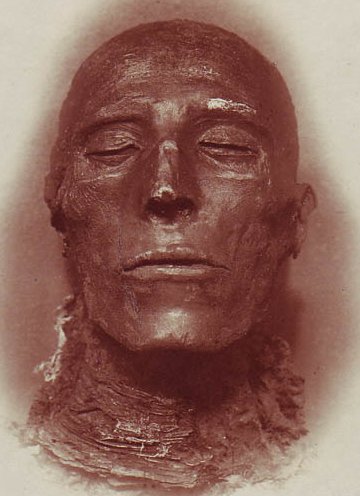

“The Mysterious Mummy” marked Sax Rohmer’s first appearance in print. Only 20 years old at the time, Rohmer was then writing under the byline of A. Sarsfield Ward. Born Arthur Henry Ward, Sarsfield was a surname of historical repute from his mother’s side of the family which he adopted at the start of his writing career.

A preview of the story was featured in the November 19, 1903 issue of Pearson’s Weekly with the full story printed in the November 24 issue. “The Mysterious Mummy” languished in obscurity until it was reprinted by Peter Haining in the 1986 anthology, Ray Bradbury Introduces Tales of Dungeons and Dragons. Haining also included the story in the 1988 anthology, The Mummy: Stories of the Living Corpse. Rohmer scholar Gene Christie selected the story for inclusion in the first volume of Black Dog Books’ Sax Rohmer Library, The Green Spider and Other Forgotten Tales of Mystery and Suspense published in 2011.

The most interesting feature about this first foray into fiction is that it is not at all a living mummy story, but rather a straight heist caper. Rohmer later disingenuously claimed that a copycat theft was attempted in France and the thief was arrested with a copy of Pearson’s Weekly on his person featuring the story which he claimed was so good he had to risk trying it in real life. Rohmer, of course, was a terribly unreliable interview subject. While it is possible the press were more gullible a century ago, it is more likely they viewed his tall tales as good copy.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE ON FRIDAY.

Labels:

astral,

Egypt,

mummy,

occult,

pulp fiction,

Sax Rohmer,

thriller

Monday, June 23, 2014

Blogging Sapper’s Bulldog Drummond, Part Three – The Black Gang

The most striking feature of the second Bulldog Drummond thriller by Sapper is the near complete removal of humor from the proceedings compared with the frequent light touch demonstrated with the initial book in the series. There is also precious little mention of the First World War, which was such an important factor in the first book, as the focus here is much more on the reaction against the Russian Revolution and the fear of a similar communist uprising occurring in Britain during the early 1920s. Once more the influence of Edgar Wallace’s Four Just Men series is strongly felt, particularly in the first half of the book where the Black Gang are featured anonymously with no mention of their true identities.

Many critics label this second entry in the long-running series as fascist. I suppose that is an understandable reaction to a vigilante storyline in which it is suggested Britain would benefit from modifying freedom of speech to deny protection to radicals. The Black Gang is very much a Machiavellian work, but one which seeks to restore order at its conclusion by having Hugh Drummond agree to dismantle the Black Gang and let the law sit in judgment over criminals going forward. Of course with such a finale as this one wonders why Sapper bothered to take the proceedings to such an extreme in the first place.

The success Edgar Wallace enjoyed with his own vigilante series was undeniably an influence, but the author’s underlying motivation appears to have been his genuine outrage over the slaughter of the Russian royal family and the belief that those behind the Bolshevik movement were not fervent followers of communism, but rather unprincipled villains eager to exploit a utopian ideology to put themselves in positions of power. Sapper wanted to see the threat of communism put down and could only envision such a task being accomplished by private citizens working outside the law.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE ON FRIDAY.

Labels:

Bulldog Drummond,

detective,

pulp fiction,

Sapper,

thriller

Friday, June 6, 2014

Blogging Sapper's Bulldog Drummond, Part Two

The strongest scenes in Bulldog Drummond (1920) are the ones that show off Sapper’s strengths as a humorist. While it has since become commonplace to see Bondian heroes tossing off quips while being menaced by an unfailingly polite villain, it hardly compares to the way Hugh Drummond handled himself in similar scenarios. Drummond regularly displays a self-deprecating humor when it comes to his features and his intellect, yet his ability to needle villains by refusing to treat them as a serious threat displays an intelligence and understanding of the criminal mind that proves a constant source of amusement for the reader.

Drummond may start off as an independently wealthy and very bored veteran of the First World War who seeks adventure, but the character soon transforms into the head of a gang of vigilantes determined to right wrongs as they see fit. He and his gang view meting out justice without resorting to the law as their right as recently demobilized soldiers. The wartime ability to kill without fear of criminal punishment continues into their clandestine civilian activities, although they take the precaution of hiding behind masks and hoods to protect their identities when doing so.

Drummond’s gang includes his fellow World War I veterans Algy Longworth, Peter Darrell, Ted Jerningham, Toby Sinclair, and Jerry Seymour, as well as New York police detective Jerome Green. Later dubbed The Black Gang, the vigilante squad was clearly inspired by Edgar Wallace’s bestselling Four Just Men series. The secret war they wage is aimed squarely against the forces of socialism and communism to an extent that was matched only by Harold Gray’s original version of Little Orphan Annie. The anti-foreign sentiments in the first book take root around the perceived threat of foreigners altering the course of England’s political identity and economic status.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE.

Labels:

Bulldog Drummond,

detective,

pulp fiction,

Sapper,

thriller

Wednesday, May 28, 2014

Blogging Sapper’s Bulldog Drummond, Part One

Bulldog Drummond is a peculiar case. The reputation of the original novels is more maligned than even Sax Rohmer’s Yellow Peril thrillers. To be sure, “Sapper” (the pseudonym of author H. C. McNeile) expressed views that stand out as offensive even among the common colonial prejudices of Edwardian England. The reason for this is easily understood. The author’s nationalistic fervor was predicated on the belief that the only good nation was Britain and every other nationality was inferior to varying degrees.

McNeile was a “True Blue” Brit in every way. A decorated veteran of the Great War, Sapper and his characters adore England and are intolerant of everyone else. Americans are castigated for their crudeness, the French are pompous, and Germans are a vile and irredeemable people. More bigoted views will follow, but that is the extent in the first quarter of the first book in the series.

Having addressed the bad, what is it that makes the books still worth reading nearly a century later? Are they simply a document of more repressive times or do they offer value that makes one willing to overlook the reliance upon stereotypes and casual slurs? I would argue that anyone interested in the development of the thriller and pulp fiction should be exposed to at least the first four books in the long-running series. There is much that is light and entertaining in Sapper’s fiction to the extent that they often read like drawing room comedies until thriller aspects interrupt the humor.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE ON FRIDAY.

Labels:

Bulldog Drummond,

detective,

pulp fiction,

Sapper,

thriller

Sunday, March 23, 2014

Blogging Sax Rohmer’s The Island of Fu Manchu, Part Four

Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu and the Panama Canal was first serialized in Liberty Magazine from November 16, 1940 to February 1, 1941. It was published in book form as The Island of Fu Manchu by Doubleday in the US and Cassell in the UK in 1941. The book serves as a direct follow-up to Rohmer’s 1939 bestseller, The Drums of Fu Manchu and is again narrated by Fleet Street journalist, Bart Kerrigan.

The final quarter of the novel sees Rohmer really deliver the goods with Kerrigan and Sir Denis Nayland Smith successfully infiltrating the Haitian voodoo ceremony of Queen Mamaloi. While similar scenes had occurred in the past at various clandestine gatherings of the Si-Fan, the sequence most closely resembles the gathering of the followers of El Mahdi in 1932’s The Mask of Fu Manchu. Rohmer’s mastery of the art of suspense writing makes the reader believe the heroes are in genuine danger. While this is no small feat considering the number of times Rohmer had penned similar scenes in the past, part of the success here is down to the climactic revelation of the voodoo Queen Mamaloi.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE ON FRIDAY.

Wednesday, March 19, 2014

Blogging Sax Rohmer’s The Island of Fu Manchu, Part Three

Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu and the Panama Canal was first serialized in Liberty Magazine from November 16, 1940 to February 1, 1941. It was published in book form as The Island of Fu Manchu by Doubleday in the US and Cassell in the UK in 1941. The book serves as a direct follow-up to Rohmer’s 1939 bestseller, The Drums of Fu Manchu and is again narrated by Fleet Street journalist, Bart Kerrigan.

The second half of the book gets underway with Sir Denis Nayland Smith, Sir Lionel Barton, Bart Kerrigan, and the local police chief holding a council of war to discuss the enigmatic Lou Cabot. A meeting is arranged by Kerrigan and Sir Denis with the dancer Flammario who is Cabot’s former lover. Cabot is involved with the Si-Fan and has run afoul of Dr. Fu Manchu. Both the Devil Doctor and Flammario wish to see Cabot dead.

Flammario is clearly meant to recall Zarmi from the third Fu Manchu novel, but she is more bitter than she is seductive. She leads Smith and Kerrigan to Cabot’s apartment. Unfortunately, the Si-Fan had the advantage and arrived before them. The place is in a shambles and they find Cabot’s hideosuly mangled corpse. Kerrigan spies Ardatha’s ring on a shelf and knows that his lost love has fallen back into the Si-Fan’s clutches.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE ON FRIDAY.

Labels:

Island of Fu Manchu,

pulp fiction,

Sax Rohmer,

thriller,

Yellow Peril

Friday, March 7, 2014

Blogging Sax Rohmer’s The Island of Fu Manchu, Part Two

Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu and the Panama Canal was first serialized in Liberty Magazine from November 16, 1940 to February 1, 1941. It was published in book form as The Island of Fu Manchu by Doubleday in the US and Cassell in the UK in 1941.

The second quarter of the novel begins with Ardatha phoning Kerrigan before he leaves for their mission abroad. She shares Fu Manchu’s itinerary with him in the hopes he will arrange for the return of Peko, Fu Manchu’s pet marmoset. After hanging up, a confused Kerrigan learns Sir Lionel abducted the animal while being liberated from the clinic in Regent Park. Sir Denis explains both he and Barton understand Peko’s value as a hostage.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE NEXT FRIDAY.

Labels:

Island of Fu Manchu,

pulp fiction,

Sax Rohmer,

thriller,

Titan Books,

Yellow Peril

Wednesday, March 5, 2014

Blogging Sax Rohmer’s The Island of Fu Manchu, Part One

Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu and the Panama Canal was first serialized in Liberty Magazine from November 16, 1940 to February 1, 1941. It was published in book form as The Island of Fu Manchu by Doubleday in the US and Cassell in the UK in 1941. The book serves as a direct follow-up to Rohmer’s 1939 bestseller, The Drums of Fu Manchu and is again narrated by Fleet Street journalist, Bart Kerrigan.

The previous book in the series was published just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War in Europe. Rohmer chose to portray characters such as Hitler and Mussolini under thinly disguised aliases. More critically, he chose to have these threats to world peace removed by the conclusion of the book as he naively believed a Second World War would be avoided at all costs. Over a year into the war, Rohmer had to address these issues for his readers. His excuse was a brilliant one. The prior narrative had been censored by the Home Office. Bart Kerrigan was forced to alter names and events. Hitler and Mussolini yet lived.

Interestingly, Rohmer chose to pick up the story some months after the last title and reflect changes in the lives of his characters. The Si-Fan has fallen under an unnamed pro-Fascist president who counts Fu Manchu’s duplicitous daughter among his closest allies. The Devil Doctor himself has fallen from grace within the Si-Fan as he opposes fascism at all costs. This rift threatens to tear the secret society apart as much as the war was doing the same to governments around the world.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE ON FRIDAY.

Labels:

Island of Fu Manchu,

pulp fiction,

Sax Rohmer,

thriller,

Yellow Peril

Friday, January 24, 2014

The Return of Rick Steele

Last year was my introduction to author Dick Enos and his Rick Steele adventure series. I suspect this year will be the one where both author and character make real headway among fans of New Pulp. The fourth Rick Steele adventure, The Yesterday Men, was just published. If you’ve read the first three titles in the series, then you know Enos loves to confound reader expectations by delivering widely varying pulp adventures from alien invasion to the preternatural to lost civilization adventures. The Yesterday Men is both more of the same and something completely different.

Rick Steele, for those unfamiliar with the character, is a hard-nosed Korean War veteran turned test pilot who somehow can’t avoid dragging himself and his supporting cast into adventures. Rick is a likable, but imperfect hero. The 1950s setting may seem like an odd one for New Pulp. It was the end of the era for serials and pulps alike, but it was also the Golden Age of Television and adventure strips were still the rage in newspapers. It was the era when the author adored Sky King and Steve Canyon in his formative years. It marked the final heyday of the innocence of American popular culture and the Rick Steele series captures this perfectly. Rather than crafting an idealistic vision of an artificial world (like so many 1950s sitcoms and movies did), the America of the Rick Steeleseries is one where darkness hangs around every corner. The characters don’t know quite what to make of it, but the reader is all too familiar with what is to come.

TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE VISIT THE BLACK GATE.

Labels:

1950s,

bigotry,

Civil War,

Dick Enos,

New Orleans,

New Pulp,

pulp fiction,

racism,

Rick Steele,

series,

suspense,

The Yesterday Men,

thriller

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)