“The Green Mist” was the fourth installment of Sax Rohmer’s serial, Fu-Manchu first published in THE STORY-TELLER in January 1913. The story would later comprise Chapters 10-12 of the novel, The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu [re-titled The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu for its U.S. publication]. When Rohmer incorporated the story into the novel, he added linking material intended to make the book appear timely and relevant. However, the true-life Yellow Peril news items that Rohmer has Petrie recount from actual British papers of the day strike a discordant note nearly a century on.

Freed from the exotic trappings of weird fiction, the straight journalism of the era seems dated, naïve, and offensive to modern sensibilities. This phenomenon is hardly unique to Sax Rohmer’s fiction and may also be experienced in the unenlightened views on display in the earliest of Herge’s Adventures of Tintin. Making matters worse is the current vogue for political correctness that believes in burying the past rather than learning from it. The combination of these factors stands as the most challenging obstacle facing a mainstream publisher if Fu-Manchu is ever to receive the exposure the series deserves whether from a new author continuing the series or a fresh printing of the classic originals.

A century ago, such views were secondary to the consideration of good storytelling and in “The Green Mist,” Sax Rohmer delivered the goods. The story introduces us to the blustering, bombastic figure of Sir Lionel Barton. The frequently infuriating Egyptologist is Rohmer’s take on Sir Richard Burton (one of Rohmer’s strongest influences) by way of a healthy dose of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s other immortal character, Professor Challenger. The dialogue crackles every time Sir Lionel takes center stage and the character easily is one the author enjoyed sharing with his readers. Little wonder that Rohmer would come to create so many return appearances for the character as the series progressed.

Sir Lionel has brought a death warrant upon himself for his planned second expedition to Tibet. Barton is described as having been the first Westerner to visit Lhasa and to have penetrated Mecca three times disguised as a pilgrim. His visits to Tibet are said to have political significance for Barton claims to have discovered a “new keyhole to the gate of the Indian Empire!” Barton’s estate, Rowan House is a true delight. The house is packed from ceiling to floor with exotic animals, curios, and a multicultural staff that in 1913 did not signify diversity, but thrills and danger.

Barton, it is obvious, is exactly the sort of man Sax Rohmer wished to become. Rohmer spent (some would say squandered) his wealth over the years on several expeditions to Egypt. He found the life of what was once called an Egyptologist to be one of endless fascination. The idea of surrounding himself with Oriental treasures and servants is a notion that made Rohmer’s heart race with excitement.

Even though the world is a much smaller place today and the internet, the public library, and television have peeled away the mysteries of Lhasa and Tibet, Rohmer successfully conveys the excitement of a hidden world of intrigue to the modern reader. The saving grace that repeatedly spares his work the damning indictment of racism (if one actually bothers to read him before passing judgment) is Rohmer’s evident delight in exploring foreign cultures. Despite the prejudices of the colonial era, Rohmer found the exotic East to be enticing and seductive and he infects his reader with his unbridled enthusiasm. This alone accounts for his infusing his Asian villain with an integrity and dignity that inspires sympathy in the reader. While film, radio, television, and comic strips made Fu-Manchu a racist caricature, Rohmer was busy creating a complex portrayal of the West’s political enemies as people worthy of respect and capable of open dialogue. This was heady stuff in an era where Britain was still considered the greatest empire since Rome.

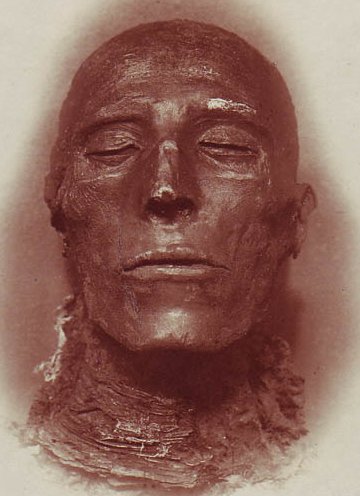

The Green Mist of the title is as fiendish a means of disposing of his intended victim as Dr. Fu-Manchu’s earlier triumph, the Zayat Kiss. Mummies, treacherous man servants, mistaken identities, and red herrings abound in this delightful entry in the series. Yet, more than successfully working his established formula, Rohmer provides surprising character development along the way.

Fu-Manchu’s still nameless slave girl who has stolen Dr. Petrie’s heart moves from the scantily-clad fantasy harem girl that owes much to Sir Richard Burton’s translation of 1001 Arabian Nights to become a realistic and sympathetic portrayal of slavery in the modern world with a depiction of the cruelty and terror of such miserable lives. This was not typical British pulp fiction of 1913, but Rohmer would certainly still be expected to comply with type by having a chivalrous Petrie rescue the fair damsel in distress. Instead, he again breaks with tradition by having Petrie respond in a realistic fashion suggesting they notify the police and let the authorities handle the situation. Petrie stands by helplessly while the woman he loves returns to her master fearing a worse punishment or death if she does not obey. In this stirring instant, all of the exotic fairy tale fantasy melts and Rohmer leaves his reader with the reality of an unjust world. It is a sobering moment that makes “The Green Mist” all the more powerful for its inclusion.

.jpg)