“Karamaneh” was the sixth installment of Sax Rohmer’s serial, Fu-Manchu first published in THE STORY-TELLER in March 1913. The story would later comprise Chapters 16 and 17 of the novel, The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu (re-titled The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu for U.S. publication). The story opens with Nayland Smith, Dr. Petrie, and Inspector Weymouth preparing a dragnet around the area where Dr. Fu-Manchu is known to have a base of operations. They have no illusion that they will capture the doctor himself, but hope to round up enough of his minions to deal a significant blow to the enemy.

Smith and Petrie are among a dozen Scotland Yard men combing the area. As they pass by a gypsy encampment, Smith recognizes one of the gypsies as a disguised dacoit who is wanted for murder in Burma (where Smith serves as police commissioner). While they fail to apprehend the man, they succeed in capturing the female gypsy before she can escape. The disguised gypsy woman turns out to be the mysterious slave girl who has repeatedly saved Petrie’s life since Smith first involved him in the affair. Rohmer does an excellent job in conveying Petrie’s mixed feelings of compulsion and revulsion when faced with this dangerous and exotic woman.

The reader shares Petrie’s ambivalence towards this complex character. She is beautiful and graced with a foreign otherness that defies precise identification and she has risked her own life several times in order to save Petrie, yet she has also willingly participated in the murder of countless other innocent men. Rohmer makes much of her unabashed stare that few men would be able to meet. Petrie is fascinated with her, but also feels ashamed that the object of his affection is opposed to all that defines a British subject at this point in time.

Much has been made of the power of sex appeal in Rohmer’s stories. It is certainly true that his fiction was more sexually-charged than many of his contemporaries, but it is not really what is at work here. The sexuality is part of the larger canvas that blankets Rohmer’s fiction. His characters defy the simple categorizations of Edwardian viewpoints. His protagonists are flawed and his villains frequently display honorable, even admirable qualities.

Nayland Smith seems representative of all that is considered proper in the British Empire: a colonial administrator who knows right from wrong and never wavers in his mission. Yet, strangely it is Smith’s re-entrance into a simple suburban doctor’s world that turns it upside down not in bringing excitement to what was routine (as is the case with Sherlock Holmes’ introduction to Watson with his previously dull and ordinary existence), but in coloring Petrie’s worldview in shades of gray where once everything appeared to be black and white. Rohmer’s great strength as an author lies in upsetting his reader’s perceptions of morality and loyalty. His characters end up following their hearts and finding their own moral compass for the world they know is an illusion compared with the larger, more complex world outside Britain’s dreams of a global empire.

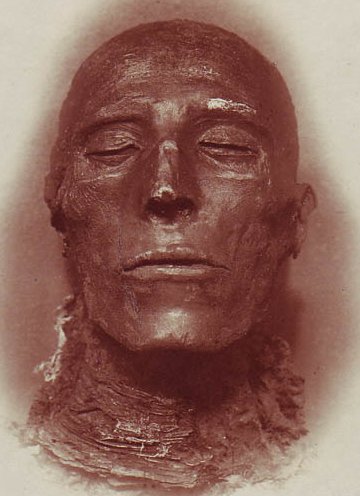

Karamaneh, as we learn she is called in this story, appears at first to be the classic femme fatale. One can detect the prototype of Bond girls yet to come in these stories that a youthful and impressionable Ian Fleming devoured. What sets Rohmer’s work apart from most pulp fiction is that his Bad Girls can also be Good Girls and that their seeming immorality can be a direct result of their past or ongoing victimization. This is the case in Karamaneh, the girl of apparent dual Egyptian and European parentage who is alternately merciful and merciless as she sees best. She is the sex slave who is also the willing victim.

Rohmer has previously shown us that the life of the exotic Arabian Nights slave girl is also one of cruelty and abuse. He now complicates matters by showing us that as a tool of her master; Karamaneh is very effective provided her emotions remain detached. This was heady stuff in 1913. Rohmer gives us mature themes that he handles with surprising taste and deftness that allowed it to breeze by the heads of those readers who were less worldly.

Karamaneh is openly critical of Smith and Scotland Yard’s effectiveness, pointing to those they have failed to save over the course of the previous five stories as justification of why she refuses to place her fate in their hands and cooperate fully with the authorities. Of course, Petrie and the reader also learn it is the life of her brother that keeps her bound to Dr. Fu-Manchu. She speaks again of their older sister who died when they were children being transported by Arab slavers across the desert. Petrie considers the thought of a flourishing slave trade in 1913 to be fantastic, but Rohmer clearly wants his readers to accept the reality of such situations no matter how removed it appeared to the average English or American at the time.

Rohmer has taken the stuff of fantasy and injected heavy doses of reality, but not at the expense of his reader’s enjoyment. That is walking a tight rope for even an experienced author, it was quite an achievement considering this was to be Rohmer’s first published novel. Despite the episodic nature of the first three Fu-Manchu mysteries, Rohmer set the bar high with complex characterizations that challenged his readers to think outside the conventional parameters their society was built upon. Without the racist stereotyping and cardboard characters of the many adaptations in other media weighing it down, the series might rival Sherlock Holmes today in terms of both popularity and critical assessment if its strength were measured on Rohmer’s literary accomplishments alone.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment